In Hachioji, western Tokyo, in a lab at Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Sciences, a researcher called Kazuya Watanabe is researching bacteria. And no, I am not talking about the kind that makes you sick. Professor Watanabe is researching a special type of bacteria found in soil and mud that can generate electricity: electrogenic bacteria. He is even trying to find the super-bacteria amongst electrogenic bacteria that generate exceptionally large amounts of electricity. Professor Watanabe usually calls these “super-electrogenic bacteria”.

Actually, there are already some species of bacteria known today that could be called super-electrogenic bacteria. However, Professor Watanabe believes there may be even better ones somewhere in Japan. He hopes that if he can find them and we can use them to generate electricity in earnest, they will become a new form of sustainable electricity.

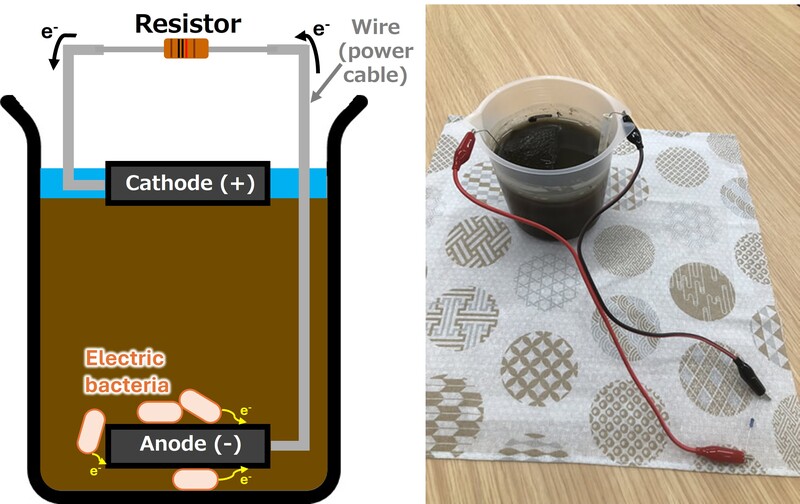

Therefore, Professor Watanabe and his team of researchers and students have been sampling many different soils. They mix the soil with a sufficient amount of water and put it in a container to create “mud batteries”. When one of these mud batteries generates an exceptionally high amount of electricity, that may be a sign of the presence of super-electrogenic bacteria. The professor and his team then isolate those bacteria for further research.

Professor Watanabe and his team have continued their research like this for years, but they never managed to take samples all over Japan. So they opened a satellite lab at the Miraikan research area and started the project, “Let’s all hunt for super-electrogenic bacteria!” together with Miraikan’s science communicators in 2021. In this project, middle and high school students throughout Japan make mud batteries using mud or soil samples from their neighborhoods, and research their electricity-generating potential just like Professor Watanabe.

Now, four years later, we have already finished the fourth edition of “Let’s all hunt for super-electrogenic bacteria!” However, it turns out that it is not easy for middle and high school students to research electrogenic bacteria in the same way as researchers like Professor Watanabe.

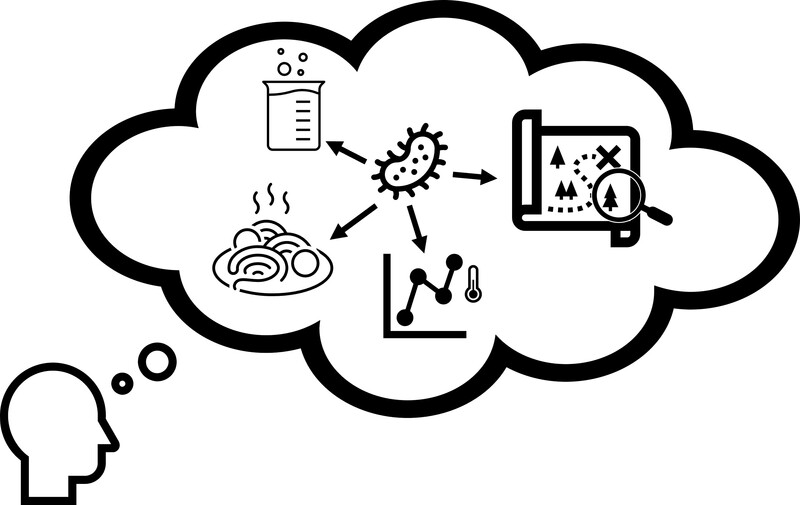

For example, how do you know where to find electrogenic bacteria? What do they even feed on? How much water should you add to your mud battery and should you submerge the cathode completely? And, importantly, how do you analyze your research data and calculate the amount of electricity your battery is generating?

All of these questions are strongly related to creating hypotheses, setting up experiments and analyzing data – essential aspects of conducting research.

To answer all these questions, help the participants get started, and assure everything went well throughout the project, we took extra measures this year. Like in previous years, participants could consult with student mentors who are active at Professor Watanabe’s lab. But this year we also added a kick-off lecture, especially for first-time participants.

Professor Watanabe, enthusiastic as always, explained about electrogenic bacteria’s ecology and way of living. I (Miraikan science communicator Serah), too, told the participants about my own first experience making a mud battery last year. I just scooped up some soil from Miraikan’s back yard without thinking about whether that was a place where electrogenic bacteria would live, and completely drowned my cathode, depriving it of the oxygen needed to let the electrons sent by the electrogenic bacteria react, thus making an extremely weak mud battery. Whoops.

The kick-off lecture got everyone started on their experiments, but then comes the next hurdle: analyzing data. Last year, many participants struggled a lot trying to determine the maximum power output of their batteries from the research data. So this year, we renewed the research manual and added an interim report meeting, where participants presented their progress and early calculations. That way, there was still time to fix errors if necessary.

Fortunately, it seemed that the kick-off lecture and renewed manual already had an effect: this time most participants managed to do the calculations correctly straight away. Moreover, the interim report meeting gave participants the opportunity to see how and what others were doing and get advice from the student mentors so that they could further improve their research.

Finally, we held the final report meeting in November, where the participants shared amazing results, amongst which were some very interesting and rare samples and extraordinarily strong mud batteries. There were also some who had chosen very unique research questions. For example, “what if I put rice bran in a mud battery?” “what if I use mud from the deep sea?” “hydrangea flowers change color depending on the soil pH level, so what if I compare soil with different pH levels, using hydrangea flowers as indicators?” “what if I place mud batteries in an incubator and compare their performance at different temperatures?”

Hearing all of the participants’ presentations, Professor Watanabe was happy to see how many of them had managed to collect reliable data. He is also planning to further investigate mud batteries from a number of participants at his own lab, especially ones that had a high maximum power output and rare samples like the deep sea mud, collected at a depth of 800 meters.

Actually – perhaps because of the information and ideas from the kick-off lecture – it seems that the participants put more thought into selecting samples than usual, resulting in a larger number of strong mud batteries than previous years. Professor Watanabe says that there were so many interesting results that he and his team will be struggling to keep up with the extra investigations and isolating potential super-electrogenic bacteria from this year’s strong mud batteries.

Of course, there were also a lot of things that participants (and experts) do not yet understand clearly, as well as mud samples that generated little electricity. For example, soil from an agricultural field mixed with rice bran had a maximum power output as large as 68 mW/m2, while the same soil without rice bran yielded no more than 7 mW/m2. (Usually any output over 20 mW/m2 is considered an indicator of the possible presence of super-electrogenic bacteria.) Seeing this result, one would think that rice bran did the trick, but the very same team of participants did the same experiment with soil from a rice field, resulting in a maximum power output of 7 mW/m2 with and 44 mW/m2 without rice bran – quite the opposite result!

Also, since electrogenic bacteria feed on organic matter, which makes water look murky, places with very clear and clean water should not have many such bacteria. But one of the participants found that a mud battery containing live shellfish, sampled at the bottom of a clear stream, had a high maximum power output. While discussing this result in the final report meeting, a new hypothesis came up: perhaps the shellfish were collecting what little organic matter there was in the water and providing it to the mud through their feces. This idea was new even to Professor Watanabe.

In this way, Professor Watanabe learned about the electricity-generating potential of many more types of mud than he could investigate with just his team, and the participants learned how to research electrogenic bacteria by participating in “Let’s all hunt for super-electrogenic bacteria!”. A number of participants even said that they are planning to further investigate hypotheses that came up during the final report meeting.

In the end, I think that everyone joining forces to investigate mud batteries has truly helped advance super-electrogenic bacteria research, just like the project’s name suggests. I am already looking forward to next year’s mud batteries and experiments, as well as the day that we will find new super-electrogenic bacteria, along with Professor Watanabe and all participants!